This is an excerpt of an email I sent (12 December 2022) to representatives of the New Zealand Space Agency, which is a part of New Zealand’s Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. This was to highlight the areas in which I have active research or see potential areas of research overlap with NASA. This summary was prompted by the then interest in supporting NZ-NASA collaborative research. The following list of projects is, of course, not a complete list of NZ-NASA projects or linkages — it is only a list of projects in which I am involved or of which I know. MBIE funding to support NZ research involving NASA must find alignment with the Aotearoa New Zealand Aerospace Strategy. I have, where possible, shown where that alignment can be made.

The research collaboration arrangement between NASA and MBIE was solidified in 2023 around a limited range of research, those of “of natural hazards, water and climate modelling, environmental monitoring, and biodiversity”. The funding was provided via MBIE’s Catalyst: Strategic — New Zealand — NASA Research Partnerships 2023. Regrettably, none of my research areas I list below have strong resonance with these selected topics.

EXCERPT BEGINS (date of writing 9 December 2022)

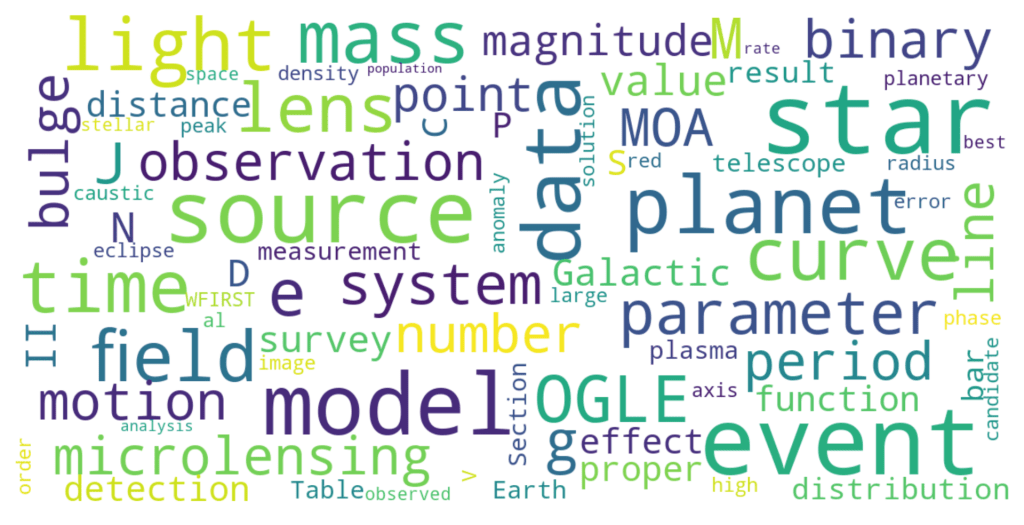

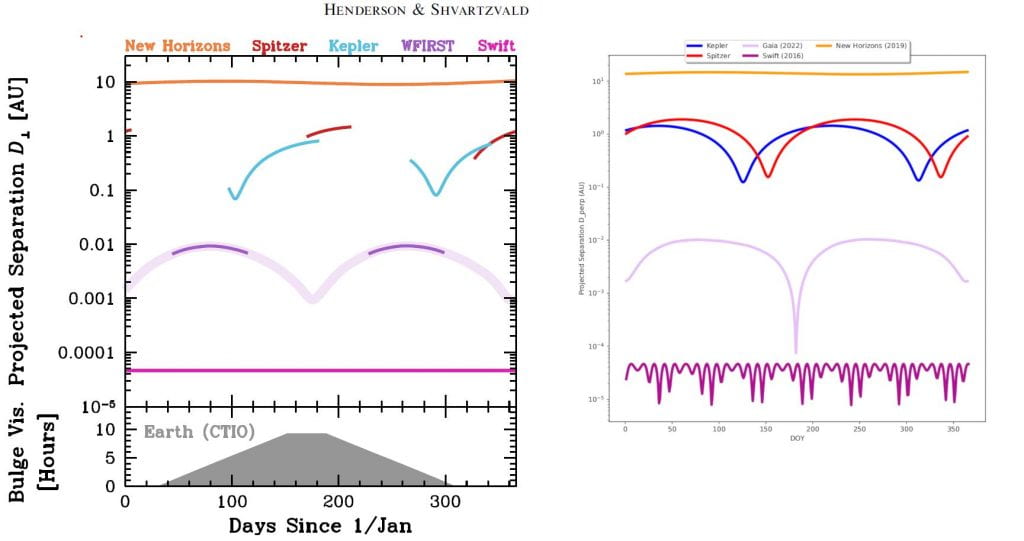

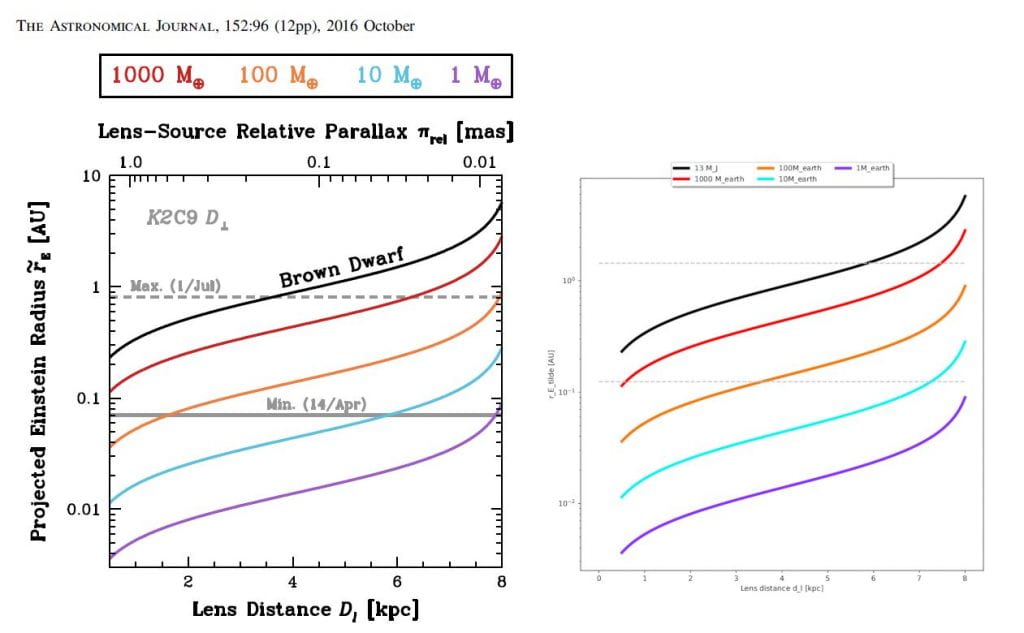

The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope (NGRST, formerly WFIRST)

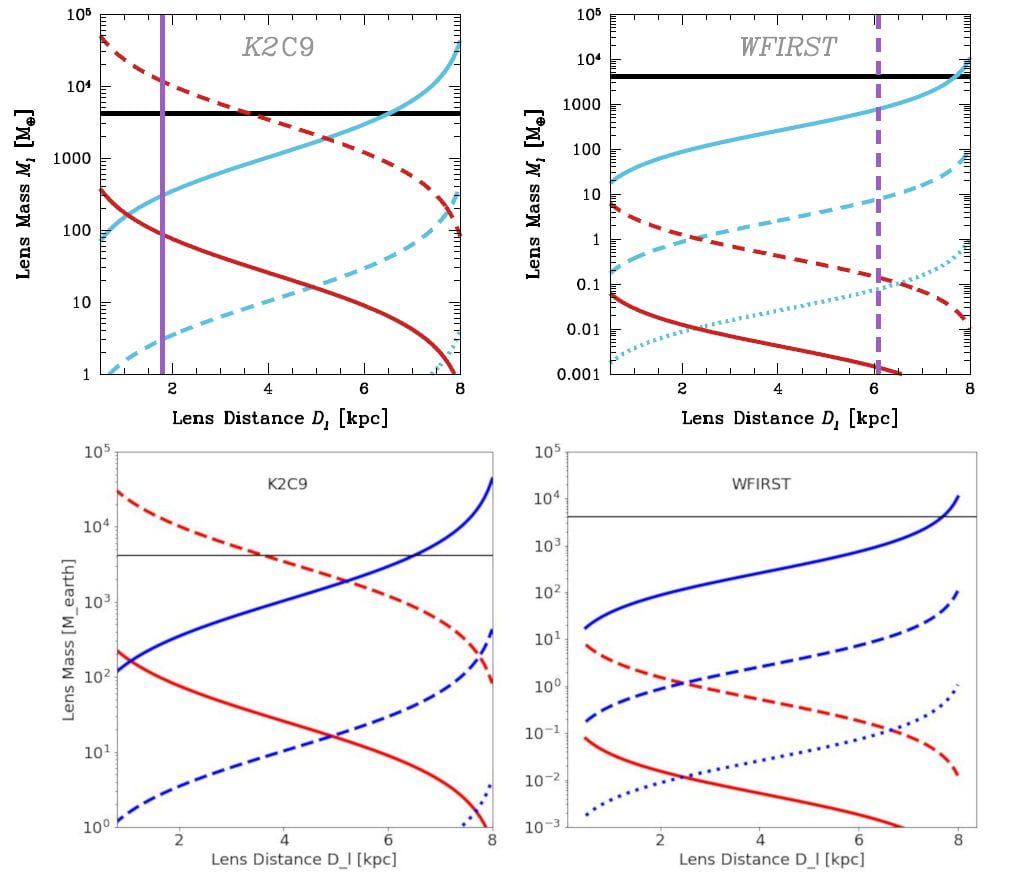

The Roman telescope will be the first space telescope dedicated to the use of gravitational microlensing for the discovery of extra-solar planets. New Zealand researchers have been active in this field for over 25 years. Members of the NZ-Japan-US Microlensing Observations in Astrophysics (MOA) collaboration are also involved with the NGRST microlensing programme. Principal among these is Professor David Bennet (NASA/GFSC). I have been working with Dave for as long as I have been a member of MOA, which is now over 20 years. Regrettably, this research finds resonance with none of the goals in the Aotearoa New Zealand Aerospace Strategy. However, one might argue that supporting New Zealand’s engagement with such a high profile NASA mission would support MBIE’s aim of [g]rowing an innovative and inclusive space sector. On that website, take a look at the evocative and inspirational image of the young person using a telescope. Imagine upgrading it with an image comprising NZers engaging in research with NASA’s flagship Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope!

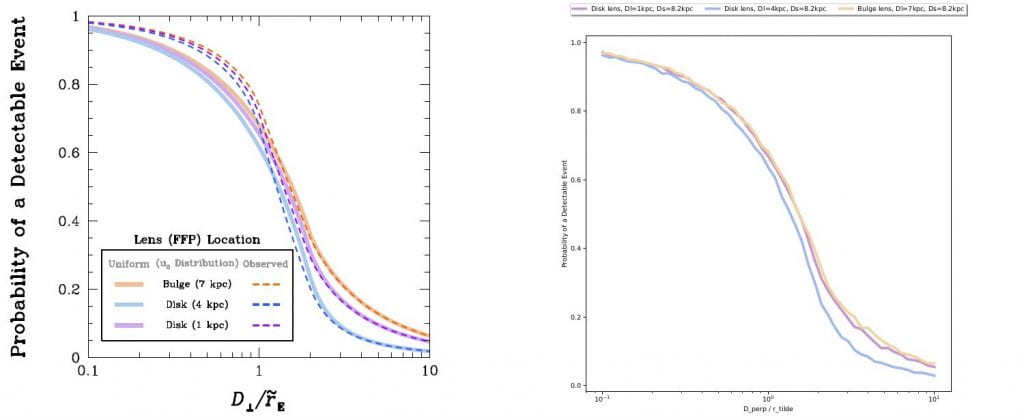

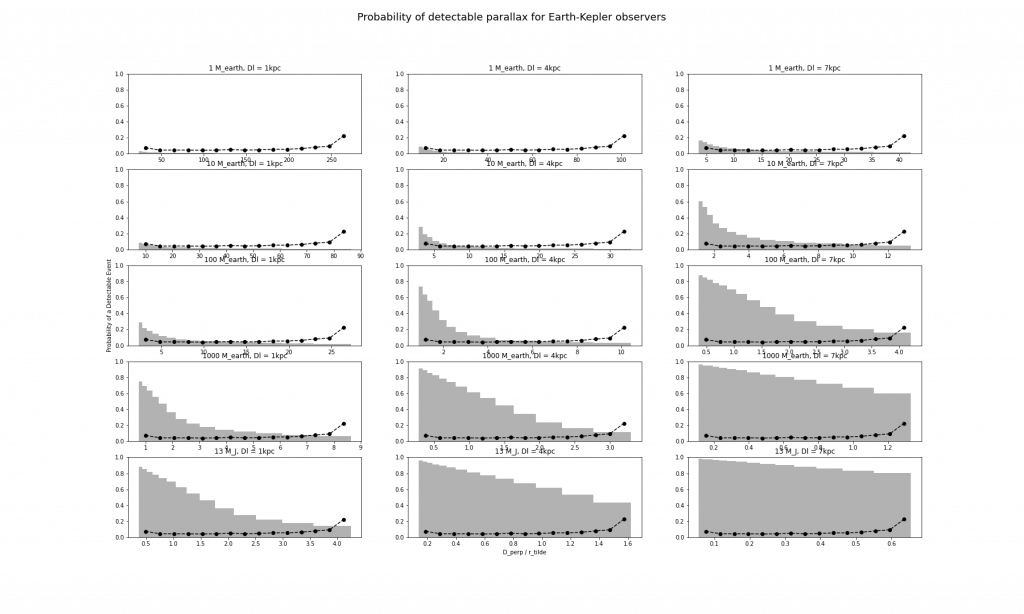

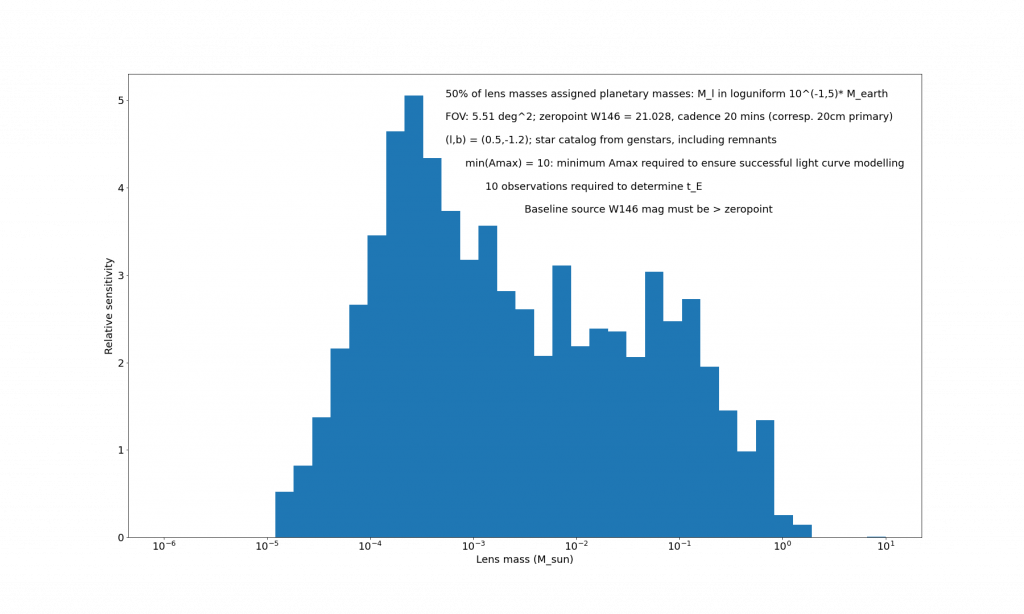

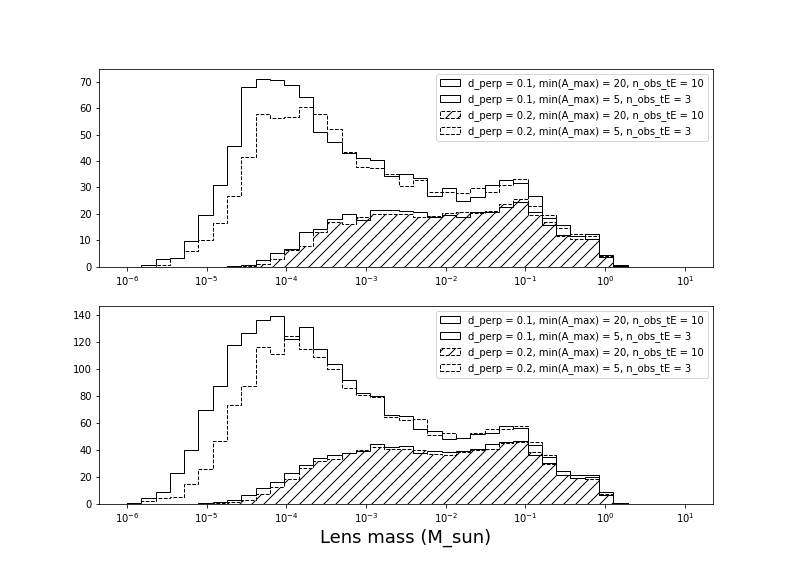

NASA CLEoPATRA

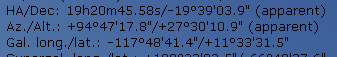

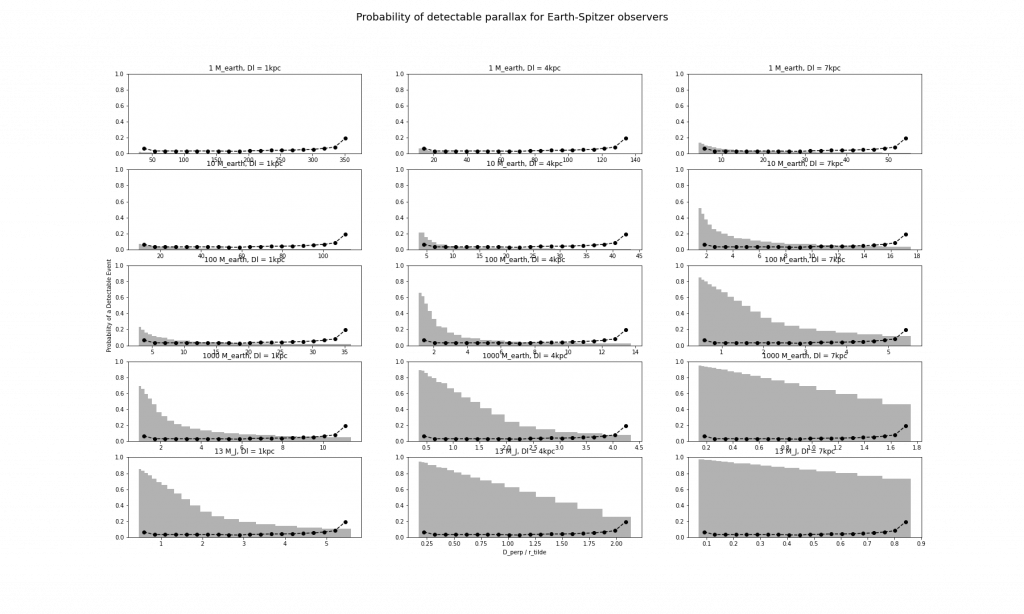

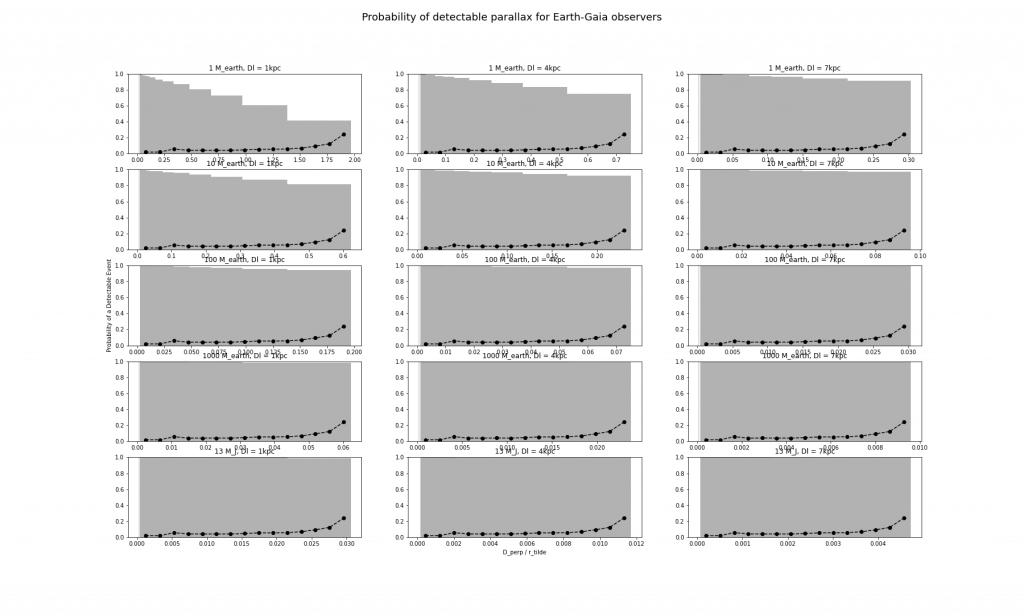

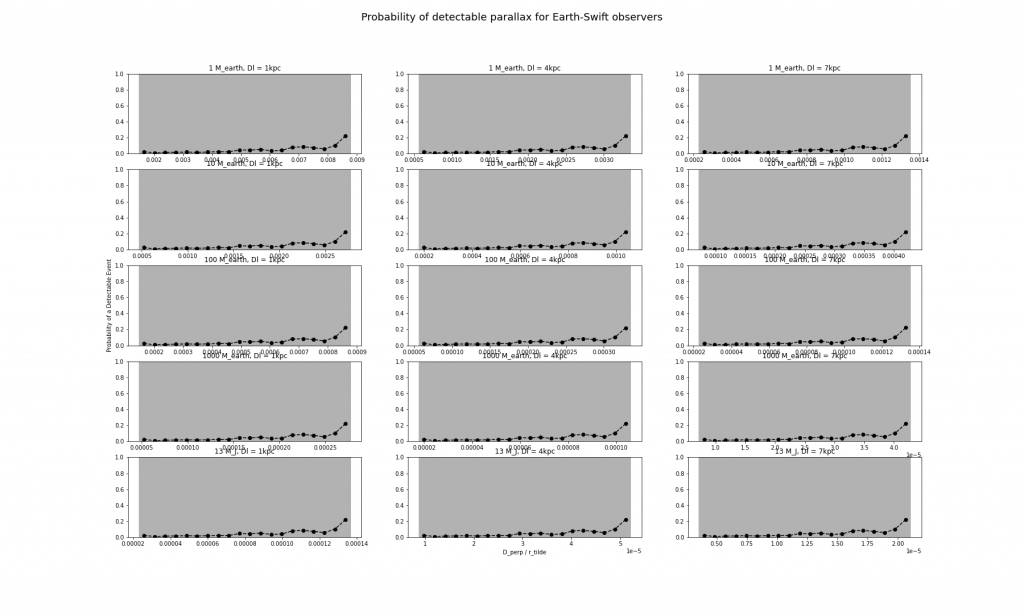

I am funded through a grant to Dr Rich Barry (NASA/GFSC) to perform preparatory simulation work for the Contemporaneous LEnsing Parallax and Autonomous TRansient Assay (CLEoPATRA) space mission concept. CLEoPATRA is designed to provide variable-baseline simultaneous microlensing parallax measurements for NASA’s flagship Roman Space Telescope mission and for terrestrial telescopes.

Free-space optical communications

The MBIE-DLR Catalyst grant for FSOC which I am leading is making progress. Advisers to the Australian Optical Communications Ground Station Network Working Group — of which we are a part — include Ed Kruzins, who works for the CSIRO NASA Operations & Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex (the Deep Space Network). NASA conducts research into optical communications for deep space exploration, and this is an area into which New Zealand could expand, in conjunction with NASA. An interesting opportunity exists in which the Warkworth 30m radio dish could be teamed with an optical communication terminal to conduct hybrid communication experiments with NASA spacecraft. I had a recent discussion with Robin McNeill (Space Operations New Zealand) about the prospects of using Warkworth as part of an expanded DSN. This work matches Strategy Goal 4: Actively support a permanent human presence in space.

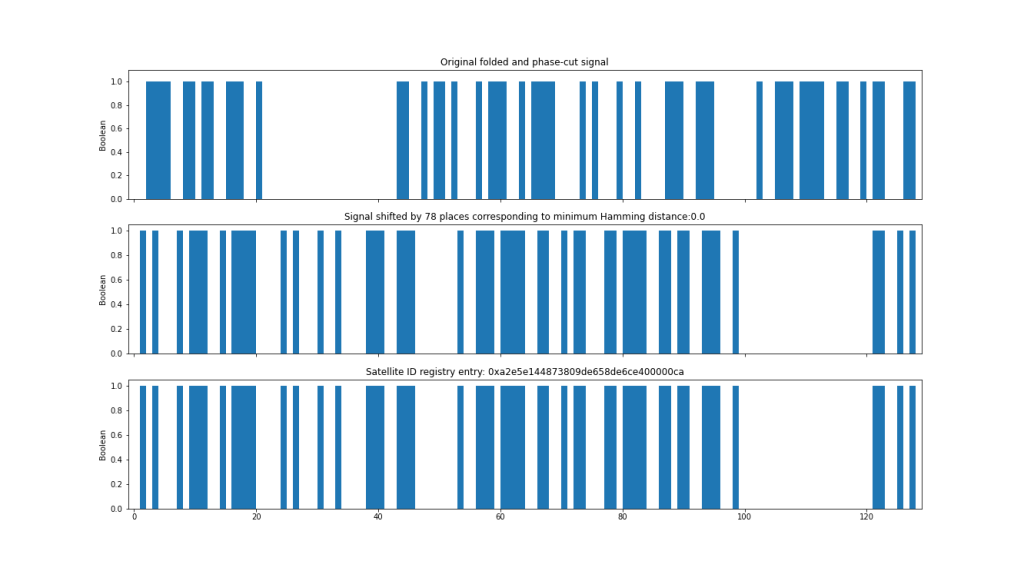

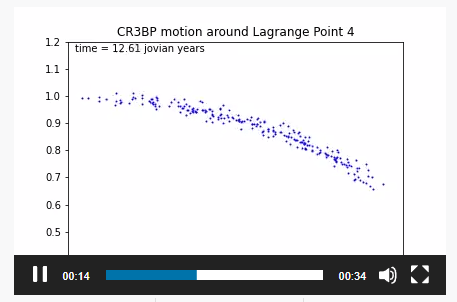

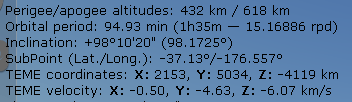

Space Situational Awareness

One area in which our optical communication research could be expanded is into the optical imaging of space assets and debris. Steve Weddell and his team at UC are active in this area. As part of my FSOC work, I am aiming to develop infrastructure to mirror the capability that the DTA has for tracking space craft. This work would naturally service the need of SSA orbit determination and trajectory analysis, but it would also provide valuable information for those of us interested in quantifying the effect of satellites on the night sky — work on which I am involved along with Dr Michele Bannister, UC. The optical tracking of space assets and debris is an active area of research at NASA. Research into making and using optical observations of space debris and assets resonates strongly with Goal 3: At the forefront of global sustainable space activities.

Planetary Defence and Space Weather

Michele Bannister (UC) and Craig Rodger (UO) conduct research into the space environment. Michele has projects into environmental degradation, and Craig researches space weather. Both of these are areas in which NASA is active. I note that Michele most recently was involved in using the MOA 1.8m telescope to attempt observations of the NASA DART mission, following its impact into the asteroid Diamorphos, as part of its planetary defence programme. I would argue that Goal 4: Actively support a permanent human presence in space, encompasses this class of research, which supports the continued human presence in space as inhabitants of planet Earth in the face of astrophysical hazards.

Mars Surface research

Professor Kathy Campbell has engaged with NASA in relation to the choice of landing sites for Mars surface sample return missions. Kathy and I are part of the Executive Team of Te Ao Mārama Centre for Fundamental Inquiry. At our recent workshop, we discussed the prospect of developing links with NASA in astrobiology research.

Balloon Projects

A cheap and fast route to space is via balloon launches. NASA’s Scientific Balloon Program has been active for years in New Zealand. I would be very keen to see links developed with the Program, as this would be a means by which New Zealand could engage with space projects at lower cost, and with shorter timeframes than through orbital space missions.

NASA’s Small Satellite Mission Directorate

In the past I have spoken with Christopher E. Baker (Small Spacecraft Technology Program Executive within the Space Technology Mission Directorate) about New Zealand working with NASA on small satellite development.